This piece was first published on ExplosivePolitics and MappingSecurity.

On June the 5th, it will be exactly three years since Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald wrote the first article based on the trove of secret documents disclosed by the now famous NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. Three years that saw the unfolding of an unprecedented controversy on the surveillance capabilities of the world’s most powerful intelligence agencies, thanks to the combined work of investigative journalists, computer experts, lawyers, activists and scholars. Since 2013, France is the first liberal European regime to undergo a vast reform of its legal framework regulating secret state surveillance. What follows is a reader’s digest of research presented at the 7th Biennial Surveillance & Society Conference.

Update (March 2017): This research has been published by the journal Media and Communication in a special issue on « Post-Snowden Internet Policy » (pdf).

For many observers, the first Snowden disclosures and the global scandal that followed held the promise of an upcoming rollback of the techno-legal apparatus developed by the American National Security Agency (NSA), the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and their counterparts to intercept and analyse large portions of the world’s Internet traffic. State secrets and the “plausible deniability” doctrine often used by these secretive organisations could no longer stand in the face of such overwhelming documentation. Intelligence reform, one could then hope, would soon be put on the agenda to crack down on these undue surveillance powers and relocate surveillance within the boundaries of the rule of law. Three years later, however, what were then reasonable expectations have likely been crushed. Intelligence reform is being passed, but mainly to secure the legal basis for large-scale surveillance to a degree of detail that was hard to imagine just a few years ago. Despite an unprecedented resistance to surveillance practices developed in the shadows of the reason of state, the latter are progressively being legalised.

This is the Snowden paradox.

France: Mass-surveillance a la mode

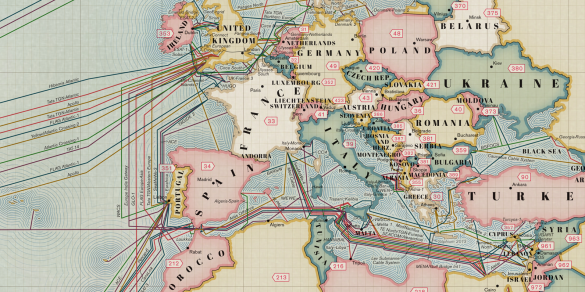

France is a good case in point. Before the adoption of the Intelligence Act in the summer of 2015, the surveillance capabilities of French intelligence agencies were regulated by a 1991 law. In the early 1990s the prospect of Internet surveillance was still very distant, and the law was drafted with landline and wireless telephone communications in mind. So when tapping into Internet traffic became an operational necessity for intelligence agencies at the end of the 1990s, it developed based on secret and extensive interpretations of existing provisions (one notable exception are the provisions adopted in 2006 to authorize administrative access to metadata records for the sole purpose of anti-terrorism). From 2008 onward, the French foreign intelligence agency (DGSE) was even allowed to spend hundreds of millions of euros to tap extensively into international fibre optics cables landing on French shores.

French officials looking back at these developments have often resorted to euphemisms, going on record talking about zone of “a-legality” to describe this secret creep in surveillance capabilities. Although “a-legality” may be used to characterize the legal grey areas in which citizens operate to exert and claim new rights that have yet to be sanctioned by either the parliament or the courts – for instance the disclosure of huge swathes of digital documents – it cannot adequately characterize these instances of “deep state” legal tinkering aimed at escaping the safeguards associated with the rule of law. Indeed, when the state interferes with civil rights like privacy and freedom of communication, a detailed, public and proportionate legal basis authorizing them to do so is required. Otherwise, such interferences are, quite plainly, illegal. Secret legal interpretations are of course a common feature in the field of surveillance. In France, they could prosper all the more easily given the shortcomings of human rights advocacy against Internet surveillance. Indeed, prior to 2013, French activists had, by and large, remained outside of the transnational networks working on this issue.

French national security policymakers were very much aware that the existing framework failed to comply with the standards of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). And so intelligence reform was announced for the first time in 2008, under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012). But the reform then lingered, which in turn created the political space for the parliamentary opposition to carry the torch. By the time the Socialist Party got back to power, in 2012, its officials in charge of security affairs were the ones pushing for a sweeping new law that would secure the work of people in the intelligence community and, incidentally, put France in line with democratic standards.

Then came Edward Snowden. At first, the Snowden disclosures deeply destabilized these plans, creating a new dilemma for the proponents of legalization: On the one hand, the disclosures helped document the growing gap between the existing legal framework and actual surveillance practices, exposing them to litigation and thereby reinforcing the rationale for legalization. But on the other hand, they had put the issue of surveillance at the forefront of the public debate and therefore made such a legislative reform politically risky and unpredictable. In late 2013, a first attempt at partial legalization (widening access to metadata) gave rise to new coordination within civil society groups opposed to large-scale surveillance, which reinforced these fears. It was only with the spectacular rise of the threat posed by the Islamic State in 2014 and the Paris attacks of January 2015 that new securitization discourses created the adequate political conditions for the passage of the Intelligence Act – the most extensive piece of legislation ever adopted in France to regulate the work of intelligence agencies.

The 2015 French Intelligence Act in a nutshell

On January 21st 2015, Prime Minister Manuel Valls turned the long-awaited intelligence reform into an essential part of the government’s political response to the Paris attacks carried on earlier that month. Presenting a package of “exceptional measures” that formed part of the government’sproclaimed “general mobilization against terrorism,” Valls claimed that a new law was “necessary to strengthen the legal capacity of intelligence agencies to act” against that threat. During the expeditious parliamentary debate that ensued (April-June 2015), the Bill’s proponents never missed an opportunity to stress, as Valls did while presenting the text to the National Assembly, that the new law had “nothing to do with the practices revealed by Edward Snowden”. Political rhetoric notwithstanding, the Act’s provisions actually demonstrate how important the sort of practices revealed by Snowden have become for the geopolitical arms race in communications intelligence.

The Intelligence Act creates whole new sections in the Code of Internal Security. It starts off by widening the scope of public-interest motives for which surveillance can be authorized. Besides terrorism, economic intelligence, organized crime and counter-espionage, it now includes vague notions such as the promotion of “major interests in foreign policy” or the prevention of “collective violence likely to cause serious harm to public peace.” As for the number of agencies allowed to use this new legal basis for extra-judicial surveillance, it comprises the “second circle” of law enforcement agencies that are not part of the official “intelligence community” and whose combined staff is well over 45,000.

In terms of technical capabilities, the Act seeks to harmonize the range of tools that intelligence agencies can use according to the regime applicable to judicial investigations. These include targeted telephone and Internet wiretaps, access to metadata and geotagging records as well as computer intrusion and exploitation (e.g. “hacking”). But the Act also authorizes techniques that directly echo the large-scale surveillance practices at the heart of post-Snowden controversies. Such is the case of the so-called “black boxes,” those scanning devices that will use Big Data techniques to sort through Internet traffic in order to detect “weak signals” of terrorism (intelligence officials have given the example of encryption as the sort of things these black boxes would look for). Similarly, there is a whole chapter on “international surveillance,” which legalizes the massive programme deployed by the DGSE since 2008 to tap into submarine cables.

As for oversight, all national surveillance activities are authorized by the Prime Minister. An oversight commission (the CNCTR) composed of judges and members of Parliament has 24 hours to issue non-binding opinions on authorization requests. The main innovation here is the creation of a new redress mechanism before the Conseil d’Etat (France’s Supreme Court for administrative law), but the procedure is veiled in secrecy and fails to respect defence rights. As for the regime governing foreign communications – which is vague enough to be invoked to spy on domestic communications –it comes with important derogations, not least of which is the fact that it remains completely outside of this redress procedure. Among other notable provisions, one forbids the oversight body from reviewing communications data obtained from foreign agencies. Another gives a criminal immunity to agents hacking into computers located outside of French borders. The law also fails to provide any framework to regulate (and limit) access to the collected intelligence once it is stored by intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

Mobilisation against the controversial French Intelligence Bill

By the time the Intelligence Bill was debated in Parliament, civil society organizations had built the kind of networking and expertise that made them more suited to campaign against national security legislation. As I show in the paper and in the online narrative below, human rights advocates led the contention during the three-month long parliamentary debate on the Bill, while benefiting from the support of variety of other actors typical of post-Snowden contention, including engineers and hackers, digital entrepreneurs as well as leading national and international organizations.

Overall, contention played an important role in barring amendments that would have given intelligence agencies even more leeway than originally afforded by the Bill. Whereas the government hoped for an “union sacrée,” contention managed to fracture the initial display of unanimity. MPs from across the political spectrum (including many within both socialist and conservative ranks) fought against the Bill, pushing its proponents to amend the text in order to bring significant but relatively marginal corrections. In the end, some of the parameters were changed compared to the government’s proposal, but the general philosophy remained intact. In June 2015, the Bill was eventually adopted with 438 votes in favour, 86 against and 42 abstentions at the National Assembly and 252 for, 67 against and 26 abstentions at the Senate. A number of legal challenges are now pending both before French and European courts against the new law.

The limits of post-Snowden contention

France’s passage of the 2015 Intelligence Act makes it an “early-adopter”’ of post-Snowden intelligence reform among liberal regimes. But lawmakers in several other European countries are now following suit. The British Parliament is currently debating the much-criticized Investigatory Powers Bill. The Dutch government has recently adopted its own reform proposal, which has also raised strong concerns. The new conservative Polish government has announced plans to expand the access of law enforcement agencies to communications data, amid heated condemnations of the regime’s “orbanization” (in reference to Hungary’s controversial Prime Minister Viktor Orban). And in Germany, the Bundestag’s Interior Committee will soon start working on amendments to the so-called “G-10 law,’” which regulates the surveillance powers of the country’s intelligence agencies.

Each country knows its own specific context, and post-Snowden contention around intelligence reform will most likely have different outcomes according to these varying contexts. As Bigo and Tsoukala highlight,

the actors never know the final results of the move they are doing, as the result depends on the field effect of many actors engaged in competitions for defining whose security is important, and of different audiences liable to accept or not that definition” (2008:8).

These field effects are exactly what made post-Snowden intelligence reform hazardous for intelligence officials and their political backers. And it may be that, in these other countries, human right defenders will have greater success than their French counterparts in defeating the false “liberty versus security” dilemma, framing strong privacy safeguards and the rule of law as core components of individual and collective security. However, the ongoing British debate or the US’s tepid reform of the PATRIOT Act in June 2015, indicate that the case of France is likely more telling than its decrepit political institutions may suggest.

In the same way 9/11 brought an end to the controversy on the NSA’s ECHELON program and paved the way for the adoption of the PATRIOT Act, the threat of terrorism and associated processes of securitization now tend to hinder the global episode of contention opened by Edward Snowden in June 2013. Securitization is provoking a “chilling effect” on civil society contention, making legalization politically possible and leading to a “ratchet effect” in the development of previously illegal deep state practices and, more generally, of executive powers.

Fifteen years after 9/11, the French intelligence reform thus stands as a stark reminder of the fact that, once coupled with securitization, “a-legality” and national security become two convenient excuses for legalization and impunity, allowing states to navigate the legal and political constraints created by human rights organizations and institutional pluralism. This is yet another “resonance” of the French Intelligence Act with the PATRIOT Act.

The proponents of the French reform were probably right to claim that it is neither Schmitt’s nor Agamben’s states of exception. But because it is “legal” or includes some oversight and redress mechanisms does not mean that large-scale surveillance and secret procedures do not represent a formidable challenge to the rule of law. Rather than a state of exception, legalization carried on under the guise of the reason of state amounts to what Sidney Tarrow calls “rule by law.” In his comparative study of the relationships between states, wars and contention, he writes of the US “war on terror”:

Is the distinction between rule of law and rule by law a distinction without difference? I think not. First, rule by law convinces both decision makers and operatives that their illegal behavior is legally protected (…). Second, engaging in rule by law provides a defense against the charge they are breaking the law. Over time, and repeated often enough, this can create a “new normal,” or at least a new content for long-legitimates symbols of the American creed. Finally, “legalizing”’ illegality draws resources and energies away from other forms of contention (…) (2015:165-166).”

The same process is happening with regards to present-day state surveillance: Large-scale collection of communications and Big Data preventive policing are becoming the “new normal.” At this point in time, it seems difficult to argue that post-Snowden contention has hindered in any significant and lasting way the formidable growth of surveillance capabilities of the world’s most powerful intelligence agencies.

And yet, the jury is still out. Post-Snowden contention has documented state surveillance like never before, undermining the secrecy that surrounds deep state institutions, prevents their democratic accountability, and helps sustain taken for granted assumptions about them. It has provided fresh political and legal arguments to reclaim privacy as a “part of the common good” (Lyon 2015:9), leading courts –and in particular the ECHR– to admit several cases of historic importance which will be decided in the coming months. Judges now appear as the last institutional resort against large-scale surveillance. If litigation fails, the only possibility left for resisting it will lie in what would by then represent a most transgressive form of political action: upholding the right to encryption and anonymity, and more generally subverting the centralized and commodified technical architecture that made such surveillance possible in the first place.